Heavyweight championship prize fights that receive coverage on network evening news appear to produce measurable increases in the U.S. homicide rate. This analysis of heavyweight championship fights (between 1973 and 1978) is perhaps most compelling in its demonstration of the remarkably specific nature of the imitative aggression that is generated. When such a match was lost by a black fighter, the homicide rate during the following ten days rose significantly for young black male victims but not young white males. On the other hand, when a white fighter lost a match, it was young white men but not young black men who were killed more frequently in the next ten days.-- Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion

Wednesday, December 3, 2014

Please let this correlation be a fluke: imitative violence edition

Sunday, November 9, 2014

Political convenience vs changes in US poverty

Then when discussing the plight of the US poor today, and especially when discussing the significance of increased inequality since around the 1970s, which is almost about the same time period as looking at America after the "War on Poverty" programs were put into place, the roles reverse. Liberals will sometimes try very hard to show that the poor have not had any improvement since then, and conservatives will sometimes try very hard to show the opposite, often by pointing out the same considerations they ignore when trying to show that the War on Poverty did not result in the poor being any better off.

I thought about this yesterday when reading a conservative book that seemed to make this contradictory switch within the very same book. People are funny.

Monday, November 3, 2014

Your life divided by the universe

There's a fair amount of psychological research showing that when we evaluate an act of charity, we don't judge it based on the absolute amount of good that it would accomplish, like the absolute number of lives. We judge it based on the amount of good it would accomplish relative to the size of the problem. For example, one study found that people cared more, and were willing to donate more money, to save 4500 refugees if they were told that was 4500 out of a camp of 11,000 refugees, as opposed to 4500 out of a camp of 250,000 refugees. In both cases the same number of lives were at stake, but in the latter case, saving those lives just seemed less worthwhile or meaningful because they seemed like a drop in the ocean. In fact, this effect even holds up in more extreme ways, in which people will save fewer lives if those lives are out of a smaller denominator, as opposed to saving more lives that are of a bigger denominator. So we're sort of focused on the ratio, which is a little depressing. But the reason that I bring this up is that, I think that the discovery of just how enormous the universe really is, is a big part of many people's sensation that life lacks meaning. So, whatever the stakes of our petty human lives ... you divide that by the size of the universe, and to our brains it just seems to lack all meaning or purpose. But I think that's just a feature of our brains. ... The way that I got past that point was to realize that our choice of denominator is arbitrary. ... Once I got to the point where the denominator feels arbitrary, then I can just pick whichever denominator allows me to continue on sensibly with my life.

Sunday, October 26, 2014

"Defending The One Percent"

Negative thought: It seems like bad framing when, after presenting the story of an equal society that became less equal in a way that benefited everyone, he says "How should the entrepreneurial disturbance in this formerly egalitarian outcome alter public policy? Should public policy remain the same, because the situation was initially acceptable and the entrepreneur improved it for everyone? Or should government policymakers deplore the resulting inequality and use their powers to tax and transfer to spread the gains more equally?". This ignores the more utilitarian answer. You can want to spread the gains through tax/transfer due to declining marginal utility, in which case it doesn't mean the new inequality is "deplored" but rather opens an opportunity to make yet another improvement to the overall situation.

Positive thought: He makes a good point when saying that, if the rising wealth of the top one percent is primarily due to rent-seeking, then it would be best to pursue policy that stops the rent-seeking rather than just try to redistribute the income after the fact.

Thursday, October 2, 2014

Birth Control vs Abortion

People are very good at believing what they want to believe. So is this trade-off ignored to keep reality as simple as they want it to be? Or do they not truly believe abortion is as bad as they say?

Wednesday, September 24, 2014

Big companies versus small companies

So here's a few interesting data points:

If you compare company sizes in various countries, innovation and economic strength are negatively correlated with the size of the small-business sector. And larger companies pay their employees more than smaller companies.

Monday, September 22, 2014

Why vote 3rd party?

As part of a collective action, your vote does have an impact. And deciding who wins is not the only possible impact. One of the main motivations of politicians and their parties is to win and keep winning. If they notice voters moving to one particular side on one or more issues, it could lead them to change their stance or priorities over time to try to win those voters. For instance, if a lot of people started voting 3rd party because of wider opposition to something generally supported by both major parties, that would likely cause some politicians in the major parties to drift in that direction. They may not see that third party as a threat to their election, but they could view that issue as an opportunity to gain votes against their opponents from the other major party and/or from within their own party in the primary elections. In that way, voting for a third party can move the world toward its ideals even if nobody from that party is ever elected.

Wednesday, September 17, 2014

Republicans, Ideology, and Special Interests

"the Republican Party is dominated by ideologues who are committed to small-government principles, while Democrats represent a coalition of social groups seeking public policies that favor their particular interests."I just don't see how that works very well. Is it small-government ideology that leads the GOP to favor agricultural subsidies? Or increased military spending? Or Medicare expansions? Those increase the size of government and coincidentally help politically important groups that vote for and fund the GOP.

Or what should we make of this:

Here's my suggestion for the GOP. Say you'll support a carbon tax if it's used to do an equal reduction in taxes on capital. Even if there were no global warming, a carbon tax would be ten times more efficient than taxing capital income. Of course the Dems would say no. And then the GOP could taunt the Dems as follows:That makes sense from the perspective of their (claimed) ideology. So why don't they do it?

"So Al Gore has convinced you guys that climate change will produce a catastrophe, and yet you'd rather engage in class warfare than solving the problem, Thanks for clarifying your priorities."

If the GOP weren't so timid on climate change they'd split the Dems right down the middle

Both major parties seek public policies that favor their interest groups. That's why they are the major parties.

Thursday, September 11, 2014

Let's cut foreign aid to 25% of the federal budget

The latest poll ... finds that the average American thinks the United States spends 28 percent of the federal budget on (foreign aid) ... In reality, we spend only 1 percent on foreign aid.-- link

... if Americans already think we give that much -- well, the least we could do is accommodate them!

We could even announce that we're obeying the American people's wishes and cutting aid to be only 25 percent of the federal budget.

...take the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) as an example... One study estimated that PEPFAR spent $2,700 for each life it saved.

Let's compare that to a major social policy meant to improve welfare here in the United States. ... Health wonks like MIT's Jon Gruber have long argued that expanding Medicaid is the most cost-effective way to expand coverage, and numerous studies (this one being perhaps the most pertinent) have found that insuring more people saves lives. Friends-of-the-blog researchers Aaron Carroll and Harold Pollack estimate that expanding Medicaid costs $1 million per life saved.

I don't want to diss Medicaid expansion: $1 million per life is actually really good compared to a whole lot of government programs. I suspect you'd get a number many orders of magnitude higher if you tried to do the same calculation for, say, a fancy new spy plane. But that would be hundreds of times less effective than increasing aid to developing countries.

Wednesday, September 10, 2014

Capital Punishment and Euthanasia

- State budgets get really tight and some really unpopular cuts have to be made, such as reducing Medicaid or something.

- Health care continues to be expensive.

- A viral news story about how much we spend on the health care of prisoners gets people upset about how it's not fair for prisoners to get things non-criminals can't afford.

- A bigger push occurs for cutting spending on prisoners and/or more widely using the death penalty for convicted murderers.

- As a compromise, convicted murders start having the option of euthanasia as a means for applying the death penalty more often but in a way that feels more humane (and of course, cuts costs).

- Although initial support was somewhat driven by wanting to reduce the number of convicted murders we have to spend taxes supporting for life, eventually people need to defend the change to themselves by viewing euthanasia in general more favorably.

- Things come full circle. A viral news story about someone in terrible pain who is not allowed euthanasia complains that, if they were only a murderer, they would be allowed to die the way they wish. Now people think it's unfair that criminals have access to euthanasia but non-criminals don't.

Tuesday, September 9, 2014

Don't compare "household" data over time

Single Americans make up more than half of the adult population for the first time since the government began compiling such statistics in 1976.... In 1976, it was 37.4 percent and has been trending upward since.-- link

This is why you should ignore any statistic that points at changes in -whatever-

Friday, September 5, 2014

You are weird.

Whenever I hear someone describe quantum physics as "weird" - whenever I hear someone bewailing the mysterious effects of observation on the observed, or the bizarre existence of nonlocal correlations, or the incredible impossibility of knowing position and momentum at the same time...-- Eliezer Yudkowsky, "Think Like Reality"

Reality has been around since long before you showed up. Don't go calling it nasty names like "bizarre" or "incredible". The universe was propagating complex amplitudes through configuration space for ten billion years before life ever emerged on Earth. Quantum physics is not "weird". You are weird.

Thursday, September 4, 2014

Cluster thinking and assuming you're always drunk

One thought experiment that I think illustrates some of the advantages of cluster thinking, and especially cluster thinking that incorporates regression to normality, is imagining that one is clearly and knowably impaired at the moment (for example, drunk), and contemplating a chain of reasoning that suggests high expected value for some unusual and extreme action (such as jumping from a height). A similar case is that of a young child contemplating such a chain of reasoning. In both cases, it seems that the person in question should recognize their own elevated fallibility and take special precautions to avoid deviating from “normal” behavior, in a way that cluster thinking seems much more easily able to accommodate (by setting an absolute limit to the weight carried by an uncertain argument, such that regression to normality can override it no matter what its content) than sequence thinking (in which any “adjustments” are guessed at using the same fallible thought process).-- from a givewell.org blog post "Sequence Thinking vs. Cluster Thinking"

I read that in June and for some reason I keep thinking about that part, probably because it helped reduce stress. I don't know how to deal with ethical and practical uncertainties that I don't know how to quantify, to the point of indecision. For instance, what if total utilitarianism and the repugnant conclusion are true/good and it's wrong to donate money toward reducing current poverty when instead I should be aiming to maximize the number of future lives? This is the type of thing that I worry about when trying to sleep at night.

So I thought the givewell post above helped a bit with not rat-holing on certain lines of reasoning that drill down into insanity. And it helped with feeling less uncertainty paralysis. And I also think it's a good way to explain the value of two-level utilitarianism over pure act utilitarianism. We all overestimate our rationality so it's good to make rules for ourselves as if we're slightly drunk.

However, if that's the right way to look at it, everyone else is drunk too, so I'm not sure how much that really justifies "regression to normality". Crap.

Wednesday, September 3, 2014

Overpopulation and Immigration

What precisely is meant by "overpopulation"? Presumably, this refers to the point where population becomes so dense that it causes average living standards to decrease. How would we determine the population density at which this would occur? I doubt there's a good way to know for sure. But population and living standards, both within our country and globally, have been rising for quite some time. And since our living standards are not increasing by some act of nature, this means that for a good amount of time now, the average extra person added to both the world and our country has had an overall positive impact on society. Unless we just hit the peak, we clearly aren't overpopulated now.

And it must not be global overpopulation that comes to mind when people voice this concern. Because a person moving here does not increase global population. In fact, being in a society of greater wealth and freedom leads to people having less children on average. So if global overpopulation is a concern, allowing more immigration from poor/oppressed countries to rich/freer countries might be a good way to deter that. It seems the "overpopulation" concern over immigration is about the overpopulation just of our country.

So how populated can a nation get without it causing a necessary drop in living standards? What if we doubled our population? Tripled? What if it increased a hundred times? Our initial intuition probably tells us that surely we'd be overpopulated well before we multiplied our population by a hundred. But why would our intuition be good at determining that?

Population densities per country can be found here. The U.S. has 84 people per square mile. That's really low by global standards. Singapore, on the other hand, has 19,863 people per square mile. That is 236 times our population density. And their average living standards are even higher than ours (by a good amount actually).

On the list of things to worry about for the U.S., put overpopulation at the bottom.

Monday, June 9, 2014

Le Pot

Kids today can't understand why old folks had a problem with gay marriage. I couldn't understand how old folks had a problem with interracial marriage. My grandparents couldn't understand why Thomas Jefferson owned slaves. Each generation has its blind spots. The next generation will be amazed that Obama enforced the medical marijuana laws even more vigorously than George Bush.

It's the kind of issue that causes giggles among the "very serious people" at places like the New York Times and WaPo. They don't personally know any families that have been destroyed because mom went to prison for violating pot laws. They just remember their college days--and none of their college friends went to prison for hosting pot parties. They don't know any of the 800,000 people arrested for violating pot laws each year. Better to focus on the "real issues," like one possible deserter being swapped for some Taliban leaders.

-- link

Thursday, May 22, 2014

Biggest Flaw in the Democratic Party, revisited

A couple years ago I posted about "the biggest flaw in the Democratic Party", where I said the overriding concern for American inequality seemed strange in comparison to global inequality/poverty. At the time it was something I was just wondering about and didn't know what conclusion I should come to. Over time I've come to take this problem more seriously, and it's one of the main reasons I feel less supportive of the Democratic Party than I used to.

Another change I've gone through over that time is a slow transition from being a Paul-Krugman-fanboy to a Scott-Sumner-fanboy. And the other day Scott Sumner made this post, which is different from the kinds of things he usually blogs about, but hit the nail on the head for the same problem that bothers me the most about the Democratic Party:

I think the biggest area where I disagree with the left is that I’m way less nationalistic than most liberals, or Pat Buchanan. If anything I care more about the overseas poor, because they are much poorer. I actually find some of the things I read on the progressive side (and on the right as well) to be almost grotesquely insensitive. In recent decades living standards in places like China, India and even Africa have grown considerably faster than in the developed world. And yet we are constantly told that inequality is getting worse and that it is the defining issue of our time. If we dissent we are scolded for being “insensitive.”

Remember the famous joke about the Lincoln assassination? It would have been insensitive to say to Mrs. Lincoln; “Yes, your husband was shot, but the play was pretty good.” In 1945 it would have been insensitive to say to a European; “Yes, there was WWII and the Holocaust, but overall Europe’s done well in the past 5 years because the economies of Sweden, Switzerland, and Spain have boomed.” And it is insensitive to say; “Yes, billions have been raised out of abject misery but inequality is getting worse because the gap between average Americans and the top 1% is widening.”

Saturday, May 10, 2014

Open Borders

Why should we grant foreigners the rights to travel, live, and work where they want? The same reason we should grant these rights to women, blacks, and Jews: They're human beings and they count. Is this asking too much? No. I'm not proposing that we give foreigners homes or jobs. I'm proposing that we allow foreigners to earn these worldly goods from willing native landlords and employers. Under current law, housing and employment discrimination against foreigners isn't just legal; it's mandatory. Why? Because the foreigners chose the wrong parents. How horrible is that?

-- from Bryan Caplan

Sunday, May 4, 2014

Does this make politics more depressing or more amusing?

The smarter the person is, the dumber politics can make them.

-- from Vox

Monday, April 28, 2014

The Repugnant Conclusion

One last post on a topic from "Reasons and Persons". I like challenging thought experiments, and The Repugnant Conclusion is one of the best for making me question my moral intuitions.

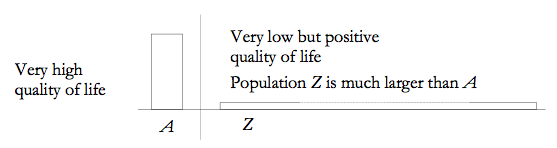

The chart above shows 2 possible worlds: A and Z. In A, everyone has really awesome lives. In Z, everyone has lives that are barely worth living, but there are way way more people in existence. Which is better? Most everyone, including myself, would agree that A is better.

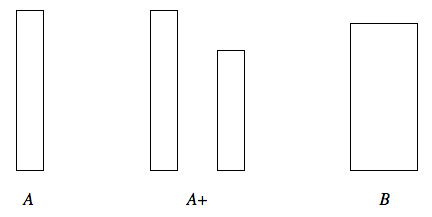

Now consider the possible worlds shown above, represented in the same way as the first picture. How does A compare to A+? A+ takes the same people with the same quality of life as in A, and adds another equally-sized group of people with a lesser but still enjoyable quality of life. For simplicity, assume that the 2 groups of people are completely isolated and have no effect on each other. How would you compare those 2 worlds? Most everyone, including myself, would find it obvious that, at the very least, A+ is not worse than A. Merely adding people with enjoyable lives, as long as they don't reduce the quality of the previously existing people's lives, surely cannot be a bad thing.

What about comparing A+ and B? They both have the same number of people. Quality of life for those people is much higher than the lesser group in A+ but only slightly lower than the higher group in A+. So the average life is better than in A+. Most of us, including myself, would say that B is a better world than A+.

So we've decided that A > Z, A+ >= A, and B > A+. Do you see the problem? If B > A+ and A+ is not worse than A, that logically means that B > A. And if you keep increasing the population and rebalancing from B, the same way you moved from A to B, you can get to Z... where there are a whole lot of people with lives barely worth living. We intuitively feel that Z is worse than A. But our intuitions on some other scenarios imply the opposite. So we have a contradiction. Which of our intuitions are incorrect?

It may be simpler to imagine, and with similarly disturbing results, to apply this same line of thought to 1 person's life, where expanding horizontally in the graphs above is adding more years to their life rather than adding more people.

I used to think utilitarianism, while difficult in practice, was extremely simple in theory. I guess not.

Saturday, April 19, 2014

Dividing your conscious self

Yet another post on something from "Reasons and Persons"...

Your upper brain, which is associated with your consciousness, memory, personality, language, etc., has two hemispheres. They are normally connected and work together to do largely the same stuff. In some cases, like a stroke, one hemisphere can die, and the remaining hemisphere still functions as the seat of consciousness for the person (although they suddenly become bad at things like motor skills).

So normally both sides combined have one consciousness - you. But it is possible for the right side to carry your consciousness independently of the left side, and vice versa. So although we currently don't have the technical means to do so, the following case is possible:

My Division. My body is fatally injured, as are the brains of my two brothers. My brain is divided, and each half is successfully transplanted into the body of one of my brothers. Each of the resulting people believes that he is me, seems to remember living my life, has my character, and is in every other way psychologically continuous with me.

In this case, who would you be? One of them but not the other? Both? Neither? And if this is possible, then recombining them to turn 2 independent consciousnesses into 1 should also be possible. What does all this tell us about the nature of consciousness and personal identity?

Friday, April 18, 2014

Intertemporal and Interpersonal Reasons

This is another post basically just making note of an interesting section of Reasons and Persons.

"Intertemporal" means "occurring across time". We basically all accept that reasonable decisions must account for their effects on ourselves across time. If someone chooses to jump off their roof because they enjoy the sensation of falling, and then they feel miserable when 2 seconds later they break their leg, we would consider there to be something seriously wrong with them. Such a person could argue "but at the time I chose to jump it was enjoyable; why should I have cared at that enjoyable moment that my future self would be in severe pain?" We would consider that argument to be irrational and that person to be mentally unstable.

"Interpersonal" means "occurring across people". We mostly accept that taking interpersonal affects of our actions into account is covered by morality but not rationality. In other words, while we may claim that someone is morally wrong to make a selfish decision that favors themselves at the expense of others, we don't think it's necessarily irrational to do so.

But why? Why would reason extend across time but not across people? Derek Parfit (the author of "Reasons and Persons") makes the case that we should think about these the same, which seemed absurd to me at first, but after further thinking (and further explanation in the book), it has started to make a lot of sense. He claims that we should see good intertemporal decisions as under the realm of morality rather than rationality. It seems like you can make the reverse claim just as well: immoral actions are irrational. We may be instinctively inclined to care more about our future selves than about other people, but both my future self and another person matter equally from an objective/rational standpoint.

Monday, April 14, 2014

Cost/benefit analysis of voting

I've always viewed voting in a presidential election as a civic duty and celebration of an important right that is all-too-easy to take for granted, but not as something that is justified purely from a narrow act-consequentialist perspective, because the odds of our vote changing the outcome is so astronomically low. But I've been reading Derek Parfit's "Reasons and Persons", which makes a compelling case why that may be wrong (or at least, similar thinking applied to similar types of choices). That book has been full of stuff that has been changing the way I think in some form, and I'll probably make many posts about topics from it.

Basically, for the same reason that a single vote has a very low chance of changing a presidential election (i.e. it is decided by so many people), it also has a very high potential impact (because it would affect so many people), and so we have to weigh the former against the latter. In the "Ignoring Small Chances" chapter of the "Mistakes In Moral Mathematics" section of the book, it explains how you might calculate this. The expected benefit of an act is the possible impact multiplied by the chance that the act will produce it. So you calculate the value of your vote (to America) between 2 candidates, versus the cost in your time to do so, like this:

((the average net benefit to Americans if your candidate is elected) x (the number of Americans) x (the odds of your vote causing your candidate to win)) - (the cost of voting)

At the time this book was written, there were about 200,000,000 Americans, and apparently a common estimate of the chance of your vote tipping the scales in some states was 1/100,000,000. Using these numbers, the sum will be positive - i.e. voting is worth your time from a pure cost/benefit analysis - if the average benefit to Americans if your candidate wins is more than half as great as what taking your time to vote cost you. And voting doesn't cost you much.

Sunday, April 13, 2014

I don't understand govt-mandated paid vacation

Laws that require all employees to get X number of paid vacation days per year don't make sense to me. A lot of people support it, but it seems like it's based off misunderstandings of what that would really mean. I haven't read much on this so maybe I'm missing important factors that I should be considering, but here's why it sounds like a bad idea to me:

1. "Paid vacation" is meaningless. My wife is a teacher and gets summers off. When you do this, you get to choose between 2 different ways of getting paid: a smaller amount every month, or a larger amount in only the non-summer months. Either way, you get paid the same salary, but one of those is "paid vacation" and the other is "unpaid vacation".

2. When people work less, we collectively become poorer. Money is only as valuable as the goods and services you can exchange it for. Goods and services are created by people's labor. If we pass a law forcing people to work less, then there will be less goods and services. So if we pass a law that leads to less goods/services, yet somehow force everyone to get paid the same salary, we have only tricked people into thinking they are getting free vacation because the way we've really paid for it is by lowering the value of that salary.

There is a trade-off to be made between paid work and time off. In other words, even though the cost can often get hidden, vacation has a cost. Different people will value that trade-off at different points. But tricking everyone into mistakenly thinking they are getting free vacation seems like a bad way to arrive at that right mix for each person. Because vacation has a cost, the well-off have more freedom/ability to get it than the less-well-off. So the best way to provide more time off to the less-well-off, to the extent that they want it, is to help them with the means to afford it, through something like a NIT or wage subsidies or tax cuts.

Tuesday, April 8, 2014

Obama is better than most Democrats: free trade edition

"President Obama ... wants to pass sweeping trade deals with Asia and Europe. concern ... has driven the top Democrats in Congress, including Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid and House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi, to block Obama's trade agenda -- opening a major rift in the party ahead of the mid-terms."-- link

If there really is a rift in Democratic primaries around free trade, you know what side I'll be on.

"If there were an Economist's Creed, it would surely contain the affirmations 'I understand the Principle of Comparative Advantage' and 'I advocate Free Trade'."-- Paul Krugman

Friday, April 4, 2014

Wait... what does vegetarian mean?

survey asked a large representative sample of Americans whether they identified as vegetarians, and on separate occasions asked detailed questions about what they had eaten in the past 24 hours. Of those who identified as vegetarians, 64% had eaten what the study considered a non-negligible amount of meat in one or both 24 hour periods

Saturday, March 29, 2014

"The problem isn't that people aren't trying to be moral, it's that they're no good at it."

we live in a failed world. Problems like world hunger, war, racism, and environmental damage are only partly controlled even in our insulated First World countries, and in the majority of the world they are barely controlled at all. It is traditional to attribute this to “people being immoral", but in fact people are generally very moral: they feel intense moral outrage at the suffering in the world, they are extremely generous in response to certain obvious opportunities for generosity like the Haitian earthquake, and many people will, in an emergency that calls for it, sacrifice their lives to save others with only a split second's thought. And even things that are in fact repulsive, like the intensity with which people oppose gay marriage, derive from a misplaced sense that they are doing the right and moral thing; people will devote their entire careers to opposing gay marriage even though it does not hurt them personally because they feel like they should. The problem isn't that people aren't trying to be moral, it's that they're no good at it.-- link

Suffering per kg from different meats

One thing I've done, when I do have meat, is mostly choose chicken over pork/beef. I did this mainly under the assumption that chickens are probably less intelligent, or at least are biologically further from myself (the one being I can be 100% certain can suffer), so perhaps they suffer less. A secondary motivation was that beef creates more pollution than other meats.

But I just came across this estimate of how much suffering is involved per kg of a few different animal products. I don't know to what extent I agree with his calculations (yet (?)), but I've realized I've really failed to consider the size of each animal in my own thoughts for how to compare meat options. Basically, because cows are so much bigger than chickens, eating

Monday, March 24, 2014

Sunday, March 16, 2014

Open Borders Day

Consider the following fundamental reasons people often provide as justification for the laws our government should or should not make, which span the whole political spectrum:

- People have natural rights/freedoms, which the government should protect, not obstruct. What does it mean to allow someone to immigrate here? It doesn't mean granting special privileges, or making everyone a citizen. It is merely a person working for an employer at a wage agreed to by both parties, and buying or renting property to live in at a price agreed to with the seller/renter. These are things we all view as very basic rights, which the government should not infringe on without very good reason. Does the location on our earth in which a person was born qualify as a good reason for this?

- The government should follow the Constitution and its founding principles. The U.S. Constitution only explicitly granted the federal government the power to regulate naturalization (i.e. citizenship), not immigration. And we didn't have a single federal law restricting immigration until 1875. Even then, that only restricted immigration specifically for Chinese people. General immigration restrictions came in the 20th century.

- The government should alleviate wealth inequality to bring more fairness to the world. However bad you believe inequality is in our country, global inequality is far worse. The median U.S. household earns more than 93% of the world's households, while the bottom 5% of U.S. households earns more than 68% of global households.

- The government should reduce its debt. The main difficulty for our federal budgets going forward is the retirement of the baby boomer generation. Our entitlement programs mainly go toward the elderly with Medicare, Social Security, and even much of Medicaid. Even beyond the cost of public projects, there's a fundamental problem when too large a percentage of our population is too old to work. Allowing more working-age immigrants helps alleviate this. This is why the CBO estimate of the latest immigration reform bill predicts lower deficits as a result.

- The government should do what increases human well-being / makes the world a better place. Presumably you think it's good to donate money to people stuck in poverty in developing nations? We can help such people much more by simply getting our government to stop prohibiting their ability to move to more stable nations like ours. This isn't just for helping poverty. Some people live in countries in which they lack basic rights. There may be high violence, war, rape, slavery, child soldiers. By what reason can we prohibit people from fleeing those situations into safer countries?

- The government should do what grows the economy. One of the things economists across the political spectrum actually agree on is that immigration is good for the economy. A study on open borders estimated that it would double world GDP. Think of people whose innovations have greatly benefited the world, such as Bill Gates (insert another name if you disagree with that example). Notice that almost all of them had the benefit of being in developed nations. How many potential geniuses, inventors, etc were never able to benefit the world with their abilities simply because they were stuck in places where they had no chance to develop them?

Friday, February 28, 2014

Moral Dilemma: Irrational Preferences

From Stumbling On Happiness:

volunteers in one study were asked to submerge their hands in icy water (a common laboratory task that is quite painful but that causes no harm) while using an electronic rating scale to report their moment-to-moment discomfort. Every volunteer performed both a short trial and a long trial. On the short trial, the volunteers submerged their hand for sixty seconds in a water bath that was kept at a chilly fifty-seven degrees Fahrenheit. On the long trial, volunteers submerged their hand for ninety seconds in a water bath that was kept at a chilly fifty-seven degrees Fahrenheit for the first sixty seconds, then surreptitiously warmed to a not-quite-as-chilly fifty-nine degrees over the remaining thirty seconds. So the short trial consisted of sixty cold seconds, and the long trial consisted of the same sixty cold seconds with an additional thirty cool seconds...

... the volunteers' moment-to-moment reports revealed that they experienced equal discomfort for the first sixty seconds on both trials, but much more discomfort in the next thirty seconds if they kept their hand in the water (as they did on the long trial) than if they removed it (as they did on the short trial). On the other hand (sorry), when volunteers were later asked to remember their experience and say which trial had been more painful, they tended to say that the short trial had been more painful than the long one...

The fact that we often judge the pleasure of an experience by its ending can cause us to make some curious choices. For example, when the researchers who performed the cold-water study asked the volunteers which of the two trials they would prefer to repeat, 69 percent of the volunteers chose to repeat the long one - that is, the one that entailed an extra thirty seconds of pain.

Let's say that one of the people who did this experiment is forced to do one of these two trials again. He/she doesn't want to do either one, but they prefer the long one only because of this odd way our memory works. You are forced to choose one of the two for them. Which choice is the most ethical?

I don't know.

Saturday, February 22, 2014

Deficits matter when the President isn't who you voted for

I saw this graph on a Wonkblog post:

The post was trying to make a different point, but what I found the most interesting about that graph is looking at whether Republicans or Democrats are more concerned about the deficit. When Clinton was President, Republicans were more concerned. When Bush was President, that flipped. When Obama became President, it flipped again. What a strange coincidence!

Wednesday, February 19, 2014

CBO scores minimum wage increase

A popular Democratic proposal to raise the minimum wage to $10.10 an hour, championed by President Obama, could reduce total employment by 500,000 workers by the second half of 2016. But it would also lift 900,000 families out of poverty and increase the incomes of 16.5 million low-wage workers in an average week.-- NYTimes

I've made this same complaint several times before, but seriously... why don't Democrats favor an expansion of the EITC instead? The EITC targets its help better and doesn't have the downside of (probably) decreasing employment.

The common argument for wanting to raise the minimum wage with a raise in the EITC, rather than just the EITC, is that the minimum wage reduces the amount of the EITC that benefits employers rather than employees:

Research by Berkeley economist Jesse Rothstein shows that roughly 27 cents on the dollar from the EITC is passed on to employers. So there's some leakage there.-- link

But so what? After all, most economists expect minimum wage hikes to cut jobs because it increases the cost of employment for employers. This is obviously a bad thing, all else equal. When we point out that the EITC instead reduces the cost of employment, then by the same logic this will decrease unemployment. Why, exactly, is this an effect we should try to counteract?

If the minimum wage were the only possible tool for raising the incomes of the poor, then maybe I'd support the hike to $10.10 after weighing the pros and cons. I don't know. But it's not the only tool, and in comparison to the alternatives, I just don't support raising the minimum wage.

Monday, February 10, 2014

Most immigration-friendly countries

Wednesday, January 15, 2014

Our moral intuitions can be wrong

And yet we seem unwilling to accept that our intuitions can be wrong about morality. An extremely common rebuttal to any moral philosophy is to come up with a hypothetical scenario where that system of ethics would lead to a conclusion that strikes us as intuitively wrong. But so what? Even just the fact that different people have different moral intuitions should make it clear that we should expect our intuitions to be wrong in some cases.

A couple of examples:

The second half of the trolley problem is often used as a rebuttal to consequentialism. Yes, it feels intuitively wrong to push the guy in that scenario. But especially for very unrealistic thought experiments like that, we shouldn't find it impossible to believe our intuition could be wrong in that case.

The Euthyphro dilemma. I was listening to the Rationally Speaking podcast and was confused to hear the host say that the idea that morality can come from a deity is refuted by this dilemma because that would mean "might makes right". Huh? If it is true that morality is the will of a deity, then it is true that "might makes right" in that case, even though those words thrown together produce a negative intuitive reaction.

I do think pointing out unintuitive cases of anyone's moral reasoning (especially your own!) can be interesting and fun. And it's a good way to challenge whether or not you, or someone, really believes what they think they believe. But it doesn't mean the ethical system in question must be wrong.